Table of Contents:

How Do You Identify a Queen Cell?

You guessed it.

Queen cells are special cells inside the hive that raise new queens.

But why are they important?

Because they tell you a lot about your hive.

Are your bees replacing their old queen? Or are they preparing to split the colony and find a new home?

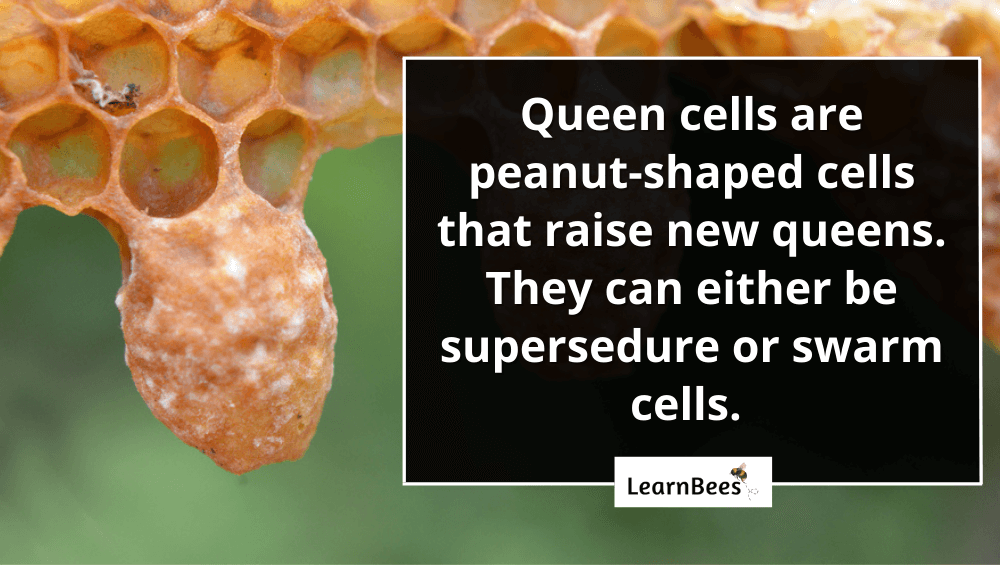

Fortunately, queen cells are pretty easy to identify. They’re typically about one inch long with a rough surface texture. Many people say queen cells look like peanuts thanks to their shape and size.

And keep in mind:

Queen cells can be found anywhere in the brood nest area. Sometimes they’re located at the bottom or sides of the comb. Other times, they’ll be scattered in the middle of the comb.

Most importantly?

Your hive will almost always make multiple queen cells. This acts as an insurance policy to ensure a new, healthy queen hatches. You may even see ten or more queen cells in a single hive.

Totally normal.

But here’s the thing:

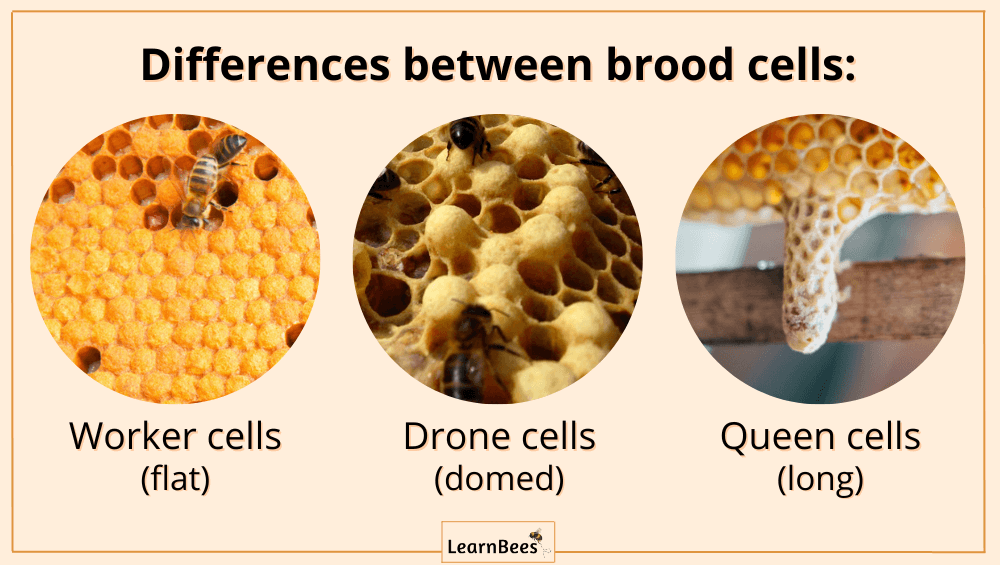

Don’t confuse queen cells with drone cells.

Drone cells develop into male honeybees, and they’re sometimes confused for queen cells amongst new beekeepers. Drones are slightly larger than female worker bees. As such, drone cells will slightly protrude out of the brood comb.

That said, drone cells are distinctly different from the large peanut-shaped queen cells that hang down off the comb.

Now you might be asking:

What’s the difference between a queen cup and a queen cell?

A queen cell is simply a cell in which a new queen is actively developing. In contrast, a queen cup is an empty cup that bees keep handy in case they need to rear a new queen. You can tilt the frame up and look into the queen cup to see if it’s empty.

It takes a sharp eye to see a bee egg, but that’s what you’re looking for.

But remember:

Most queen cups never actually become full-fledged cells that raise a new queen.

They’re simply empty cups with no larvae in them. They act as a “just in case” bee insurance policy.

Why Do Bees Make Queen Cells?

Your bees will make queen cells for one of the following reasons:

- They need to replace their ill, aging, or missing queen

- They’re preparing to swarm

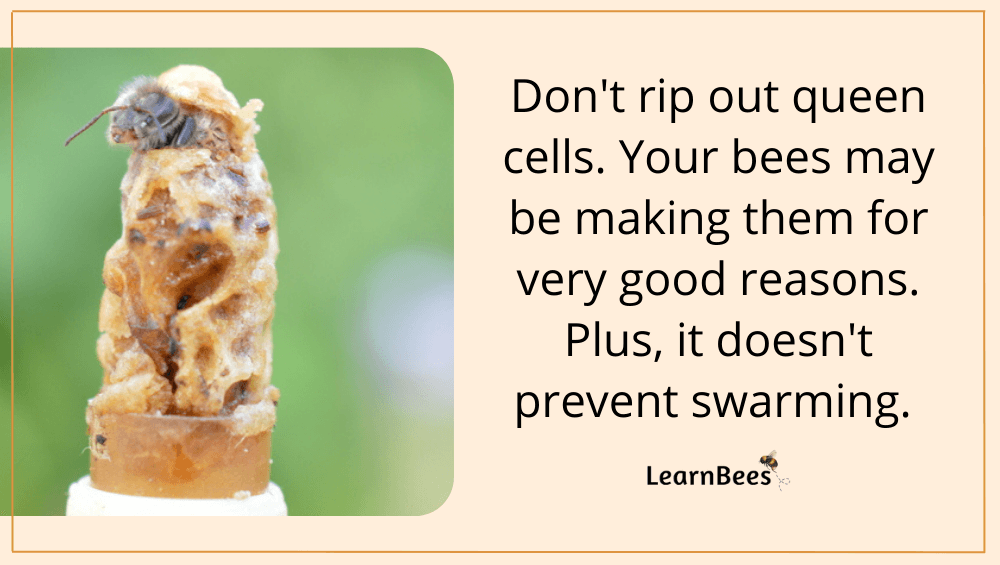

The important thing to remember is to not rush to conclusions just because you see queen cells. Some new beekeepers believe they should immediately tear down queen cells to prevent their hive from swarming.

However, this simply isn’t true.

To understand how to handle queen cells, we must first understand why the bees make them in the first place.

So let’s break down each of those reasons:

Reason #1: Your colony needs to replace their ill, aging, or missing queen

This is known as a supersedure cell.

And remember:

Supersedure cells are crucial to the survival of your colony.

Simply put, bees will replace an old or ill queen when she isn’t laying enough eggs. For example, a healthy and strong queen honeybee can lay up to 2,000 eggs daily. If a sick or old queen cannot keep up, then the colony’s future is at risk.

Queen honeybees live about two to three years, on average.

More importantly, queens only have a limited amount of fertilized eggs they can lay. So the colony will start building queen cells when it’s time to replace her.

This is a good thing. It’s a natural part of the bee lifecycle.

Additionally, your bees may produce queen cells when your queen dies unexpectedly. Maybe the queen died from disease, or a beekeeper accidentally squished her.

Either way, your bees will start rearing emergency queen cells to replace her.

You may only see one or two emergency queen cells. This is because there was a lack of suitable larvae to develop into queens.

Why?

Because bees have to choose larvae that are young enough to develop into queens. Sometimes, the bees don’t have many options of young larvae to choose from.

Don’t forget:

Bees are working on a tight timeframe.

It only takes a few short weeks for new bees to hatch. So the bees have to get to the young larva before it’s started developing into a worker bee or drone bee.

As a result, you may only have one or two emergency queen cells in your hive because the larvae options were scarce.

Reason #2: Your colony is preparing to swarm

Swarming occurs when half the colony leaves and finds a new home.

The bees produce swarming cells to raise a new queen to leave behind. Meanwhile, the swarm flies off with the old queen searching for a new nest.

Swarm cells are often found close to the bottom or side of the frames. You may see swarm cells in clusters.

Now you might be wondering:

Is swarming a bad thing?

No. Swarming is natural and crucial for the survival of bees. It’s their way of reproducing.

The idea that only “unhappy” bees swarm is a myth. Yet, many beekeepers are taught that swarming is a failure on their behalf.

This simply isn’t true.

Swarming bees are doing what they were made to do. A swarming colony is a thriving colony. It’s a colony with enough resources to split itself in half.

But, as a beekeeper, managing swarms is a part of the deal.

For example, you don’t want your neighbors to be concerned over a swarm of bees that landed in their yard. This could result in both bad news for your neighbors and your swarm. This is why most beekeepers try to minimize swarming.

What Do You Do if You See a Queen Cell?

First things first:

Don’t act impulsively.

You have to start by trying to understand why your bees are making queen cells. Don’t be too quick to remove queen cells because you might be putting your hive in danger. For instance, your old queen might’ve died, and now your colony is frantically trying to replace her.

So your first task at hand?

Try to find your queen bee.

If you can’t find her or signs that she’s been actively laying eggs, then there is a chance that she may be dead. This is where supersedure queen cells come into play. Your bees make supersedure cells to “supersede” or replace the missing queen.

Keep in mind:

Queen cells can be located anywhere – along the sides of the frames or scattered throughout the brood nest. That said, supersedure cells are often found higher up in the middle of the frames.

Additionally, your colony will also make supersedure cells to replace an old or sick queen. In this case, you should leave the queen cells alone and trust your bees to handle it.

From there, you’ll want to check back with your bees in a few weeks to ensure they’ve successfully replaced their queen. You’ll be looking for the new queen or signs of fresh brood being laid.

But here’s the thing:

It can take up to three weeks for a new queen to fully mature, mate, and start laying eggs.

Queen bees don’t start laying immediately after hatching. They need time to mature, and some may need multiple mating flights. Beekeepers have to be patient.

But that’s only part of the story.

You have to wait for your new queen to hatch first. Queens emerge 16 days after the egg is laid.

But what about preventing a swarm?

The truth is that preventing a swarm isn’t easy. It’s the honeybee’s natural instinct to reproduce. As such, beekeepers can only delay – not prevent – a swarm from happening.

If your colony wants to swarm due to over-crowding, anything you do to give them more room will help:

- An upper entrance gives your bees better ventilation and lessens congestion at the lower entrance

- Screened bottom boards also offer better ventilation – as well as separate mites from the colony

- Slatted racks offer your colony more space to cluster in the brood nest

- Empty supers allow for room above the brood nest to store honey

- Burr comb made between the frames should be cut off. Burr combs can prevent the queen from moving around easily

- Follower boards between the brood box and frames give the bees more room to cluster

- Reversing hive bodies provide space above the brood nest for honey and keep the brood nest lower

These tips may help you delay a swarm, but they aren’t foolproof. Remember, bees are hardwired to reproduce by swarming. Controlling their natural instincts can be tricky.

FAQs on Queen Cells

- What is a queen cell?

- What is the difference between a queen cell and a swarm cell?

- Should I get rid of queen cells?

- How long do queen cells last?

- Will bees destroy queen cells?

- How long does it take for bees to make a queen cell?

- Can you split a hive with a queen cell?

- Can I split a hive without queen cells?

- How many queen cells should you leave?

- Where are queen cells located?

- How often do you check for queen cells?

- What do emergency queen cells look like?

- Will laying workers make a queen cell?

- How long does it take a queen cell to lay a queen?

- Does queen cell size matter?

What is a queen cell?

People often ask:

How can you tell if it’s a queen cell? How do you identify a queen cell?

A queen cell is a cell in which a queen bee is developing.

Queen cells are larger than regular worker bee cells. They’re often about one inch long with a rough texture. You can identify a queen cell by its peanut-shaped appearance.

Additionally, queen cells can be found anywhere in the brood nest area. Sometimes they’re clustered together, while other times, they’re randomly spaced apart.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

What is the difference between a queen cell and a swarm cell?

A swarm cell is a queen cell.

Swarm cells are often made when honeybees have the natural instinct to reproduce. Swarming allows the colony to split into two separate colonies. As the cycle continues, swarming provides for more and more bee colonies to be introduced into the world.

Swarm cells can also be made when the colony outgrows the hive and need more space.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

Should I get rid of queen cells? When should queen cells be destroyed?

No.

The first thing you should do is avoid acting too quickly. You don’t want to remove queen cells that are there to supersede an old or dead queen.

Additionally, removing queen cells to prevent swarming never has been and never will be a successful way to control swarms. The bees will immediately start rebuilding queen cells as soon as you remove them.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

How long do queen cells last?

It takes 16 days for a new queen to emerge from her queen cells. Many of the queen cells are destroyed before queens hatch from them. The queen cells can be removed either by queens or workers.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

- How Many Bees Are in a Hive?

- What is Backyard Beekeeping?

- Honey Extractors 101: Everything You Need to Know

Will bees destroy queen cells? Why do bees tear down queen cells?

Yes, sometimes bees will destroy their queen cells. We don’t fully understand what’s going through the mind of bees. However, they may have simply changed their mind about raising a new queen.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

How long does it take for bees to make a queen cell?

Not long at all. The longest part is the development of the queen bee, which takes 16 days from egg to hatching.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

Can you split a hive with a queen cell?

Yes, you can try a swarm control split.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

- What is a Super for Bees?

- What Do Beginner Beekeepers Need?

- What Are the Langstroth Hive Dimensions?

Can I split a hive without queen cells?

Yes, but we recommend doing plenty of research before doing this. Also, having an experienced beekeeper to help you is best.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

More to Explore:

How many queen cells should you leave?

All of them. We don’t recommend removing queen cells as a method of swarm control. If the bees are ready to swarm, they’ll only make more queen cells after you’ve destroyed the old ones.

Research other swarm control methods that are more effective.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

Where are queen cells located?

Queen cells can be found anywhere in the brood nest area. Sometimes they’re clustered together at the bottom, while other times, they’re scattered around the middle of the frame.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

How often do you check for queen cells?

About every ten days or every time you perform a hive inspection during the warm seasons.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

What do emergency queen cells look like?

Emergency queen cells look just like all queen cells: about one inch long, peanut-shaped, with a rough texture. They’re typically found on the sides or bottom of the frame.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

Will laying workers make a queen cell? Can a worker bee lay a queen cell?

Only queen bees can lay fertilized eggs that will turn into female bees. However, once the fertilized egg has been laid, the worker bees will take it from there and begin raising a queen bee.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

How long does it take a queen cell to lay a queen?

It takes 16 days from egg to hatching for a new queen honeybee to emerge.

—> Go back to the FAQs on queen cells

Does queen cell size matter?

Queen cells will vary in size.

With that said, I wouldn’t get too hung up on queen cell size. Just because a queen cell is smaller doesn’t mean it won’t produce a nice queen. Sometimes ridiculously large cells never even emerge new queens or have just average queens.